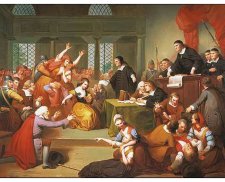

Witchcraft Trial Portrayed

From the October 31, 2009 Williamsport Sun-Gazette:

George Jacobs Sr., tried and convicted of being a warlock in 1692, hadn't a chance in Hell to mount a defense that would have enabled him to escape his fate - swinging from the end of a noose in Salem Township, Mass.

Jacobs, portrayed by Lycoming County Judge Richard A. Gray, was among the Puritan characters in a skit performed Thursday at Orlando's Restaurant here.

The witchcraft trial was re-enacted by the Charles F. Greevy Jr. American Inn of Court, an association of about 40 county and federal judges and lawyers who meet monthly to talk about issues impacting the courts.

The re-enactment provided both entertainment and a lesson in jurisprudence.

Its timeliness - days before Halloween - made it all the more appealing.

With a blood-red painted wall serving as the background at the restaurant, Jacobs declared his innocence before unscrupulous magistrates and witnesses accusing him of "cavorting with Satan."

'Possessed girls'

Jacobs defended himself against what he claimed were false accusations made by "possessed" girls in the village, some of who also were handed death sentences.

"I am as innocent as the Child born to night. I have lived 33 years here in Salem," Jacobs said.

"Once the magistrate in Salem bound over the case, he was toast," observed William Carlucci, an attorney referring to the accused witch or warlock.

Unlike today's legal system, which affords the accused the right to a fair trial and presentation of evidence gathered before a jury of his or her peers, the defendants of that day had few choices.

Those picked as "the Devil's children" could either flee the town, confess their sins, accuse someone else or deny their involvement and more than likely be hanged.

Contrary to widely accepted opinion, none of the Salemites were burned at the stake.

Yanked to magistrate court

In the skit, Jacobs is yanked into the magistrate court by the jailer, Brian Bluth, to face magistrates Jonathan Corwin, portrayed by county Judge Dudley N. Anderson, and John Hathorne, played by Alexander Smith. Each performer read from the script with vigor.

Corwin groused, pointing an accusatorial finger at the ill-fated man.

Such proceedings in 1692 Massachusetts began as investigative in nature.

The inquisition of the villagers was birthed when resident Betty Parris, 9, and her cousin Abigail Williams, 11, the daughter and niece of the Rev. Samuel Parris, began to have fits described as other-worldly and beyond epileptic in nature.

The girls screamed, threw things, uttered strange sounds, crawled under furniture and contorted themselves into peculiar positions, according to eyewitness accounts of the Rev. Deodat Lawson, a former minister in town.

The children also complained of being pinched and pricked with pins, although a medical doctor could find no evidence of any aliments. Soon, other young women in the village began to experience similar behaviors.

Target for accusations

The first three accused and arrested for allegedly afflicting Parris, Williams, Ann Putnam Jr., 12, and Elizabeth Hubbard were Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne and Tituba, a slave of different ethnicity than the Puritans and an easy "target for accusations."

The play continued with Sarah Churchwell yelling in magistrate court, "What then."

Jacobs' objections seem pointless defense. "Pray do not accuse me, I am as clear as your worships; you must do right judgments," Jacobs said, as he is accused of hurting the girl.

"Look there, she accuseth you to your face, she chargeth you that you hurt her twice. Is it not true?" Corwin asked.

"Here are three evidences," Hathorne said.

While the skit was tinged with elements of humor, it must have been a horror for the defendant.

'You tax me for a wizard'

"You tax me for a wizard, you may as well tax me for a buzzard, I have done no harm," the ill-fated Jacobs said.

Jacobs tried desperately to reason with the magistrates.

But Corwin frowned, asking him to recite the Lord's Prayer.

Jacobs, who is basically illiterate, sputters a few verses, but can't get it straight.

Despite claiming Christ suffered three times for him, he is carted away as the trial ends for the day.

Jacobs was later convicted and hanged.

Other accusations followed, and the stakes changed dramatically on May 27, 1692, when William Phips ordered the creation of a Special Court of Oyer and Terminer for Suffolk, Essex and Middlesex counties to prosecute the cases of those in jail facing charges of witchcraft.

The well-documented witchcraft trials, which can be seen in the movie, The Crucible, ended in the deaths of 14 women, along with Jacobs and four other men.

Modern kangaroo courts

After the performance, Attorney Robert Gallagher cited examples of how kangaroo courts existed long after the Salem witchcraft inquisitions and evidence exists that such accusatorial proceedings mirrored the Puritan period.

He cited two more modern examples: Brutality by the late Iraq President Saddam Hussein and the Baathist regime that held assemblies where men pointed to each other and were dragged outside only to be shot in cold blood. The chilling assassinations were captured and televised for Americans to see in horror.

Likewise, before that, Khmer Rouge and Cambodian dictator Pol Pot executed 2 million Cambodians and South Asians and journalists in mass genocide in the 1970s.

"The sad lesson is history repeats itself," Gallagher said. "But American jurisprudence is better for it."